Ep. 14: Lord of the Wind Orchestra: Johan De Meij on Hobbits, Trombones, and Self-Publishing

Episode Description:

Today I’m speaking with “Lord of the Wind Orchestra” Johan de Meij, a Dutch composer and conductor who has been self-publishing his music ever since the premiere of his symphony number one, based on the Lord of the Rings, which premiered 35 years ago this month and catapulted him to fame within the world of wind orchestra music. We had a fantastic conversation about Tolkien, creative orchestration, marketing compositions through unique titles, the history of wind orchestra music, what to do with success, and a host of other topics. His music is distributed through Hal Leonard, and a new edition of the Symphony Number one will be released next month.

Featured On This Episode:

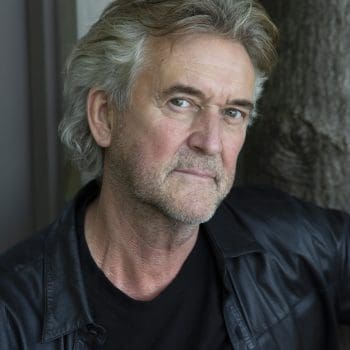

Johan de Meij

Dutch composer and conductor Johan de Meij (Voorburg, 1953) received his musical training at the Royal Conservatory of Music in The Hague, where he studied trombone and conducting. His award-winning oeuvre of original compositions, symphonic transcriptions and film score arrangements has garnered him international acclaim and have become permanent fixtures in the repertoire of renowned ensembles throughout the world.

Episode Transcript:

*Episode transcripts are automatically generated and have NOT been proofread.*

Johan de Mei, welcome to Selling Sheet Music. Hi. Nice to be here.

So this is a podcast for composers and arrangers, many of whom are self-publishing, all of whom, I think, are trying to do what you did, and that is to find their own unique spin on their music and get noticed. So I think with that in mind, we have to start with your Symphony No. 1, which is unique in a number of ways, the fact that it’s written for concert band, the fact that it’s your first piece, and the fact that it’s inspired by the material from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.

So could you talk about how that piece came to be, and especially why you wrote it, even though everyone told you not to? Yeah, exactly. We have to rewind back to the 80s. I started thinking about the piece in 1982, to be precise, and I started reading the books and making notes, etc., and I started the composing process in 1984.

And it was finished in December of 1987, so it took me almost four years to write it. And yes, this is my first piece, and when I told people in those days that I was writing a 45-minute symphony, everybody said, out of your mind, nobody’s going to play that, it’s too long. And my standard answer was, well, I know pieces of four minutes that I think are too long.

So that didn’t come across very well, because in those days, there were no pieces longer than 45 minutes or around 45 minutes, very few. Nor were there symphonies. I mean, the whole history of the symphony for wind orchestra goes back to Hector Berlioz, you know, who wrote a symphony Funèbre et Triomphale, which is a large, large piece, a great piece, by the way, with a trombone solo in the second movement, Oraison Funèbre.

And then came, there’s a Persichedi symphony, of course, the Hindemith, but that’s only like 14 minutes. Two French composers started writing serious symphonies for winds, Ilar Gorskowski and Serge Lansin. They wrote a symphony Paris, a Manhattan symphony.

And that was before I started working on my symphony. The reason I wrote a 45-minute piece was that I already had a name as an arranger in the early 80s. That all started around 1980, when I started to make arrangements of more popular music.

The most popular was, and still is, the moment for Morricone, the film music of Ennio Morricone. That became a huge hit, and it still gets played all the time. And also in the 80s, I wrote a lot of other arrangements, like the Phantom of the Opera, and also some classical stuff, Romeo and Juliet, Star Wars, etc.

But I really wanted to, just as a hobby, write my own music. And a lot of people asked me to. When I became known as an arranger, they said, well, this is great, but why don’t you start composing yourself? And I said, okay.

Had you studied composition up to that point? No, I’ve never had a single lesson in arranging or composing. It’s all self-taught. That’s incredible.

Yeah. Yeah, I never went to a teacher. Of course, I have my consultorium diploma on conducting and trombone, but not on composition.

So I did get theory and counterpoint and all that, but not on arranging and composition. I think I learned the most from two things, just playing in an orchestra or playing in a wind orchestra, what I’ve been doing since the early 70s. I’m an old man by now, if I think of those days.

But I learned a lot just sitting in an orchestra and listening and seeing what was going on. The most I learned from just reading scores from the classical masters, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Bruckner, Mahler, Sinema, Dvořák. That’s how I learned to orchestrate, just watch how the big guys do it, and there are no secrets in those scores.

Yeah, and I still love what I’m doing. It’s still my hobby. So the Lord of the Rings started as a hobby.

It was not a commission. There was no deadline, no concert planned. And I started with the fourth movement, The Journey in the Dark, because that was the chapter that captivated me immediately when I was reading it.

I could hear the music to that, that claustrophobic journey in the minds of Moria, et cetera. But as I said, everybody told me I was crazy to write a piece of that length. It’s funny that they say nobody will play it, and now it’s one of the most performed works in the literature.

And then in 1988, right after the premiere, I decided to start my own publishing company, Amstel Music, and this year we’re celebrating 35 years, Lord of the Rings and my company. And I think I was one of the first self-publishing composers, besides Jan de Haan, you know, who started De Huske, which is now Helen Lennart. He was about the same time that he started also publishing his own work.

And there’s a guy, he passed away, but his name was Guy Wolfernan, and he started his own company called, oh, Lyric Music or something, a British composer who I think was the first self-publishing composer that I know of. What do you think makes a piece of music authentic to Tolkien? And as somebody who spent a lot of time in Middle Earth and a lot of time in that material, what was it like for you to watch 15, 20 years later as the Peter Jackson movies came out, and then recently with the Amazon Rings of Power? And what’s it like for you listening to those scores and knowing that yours came first? I think it holds up remarkably well, but I’m curious on your thoughts of how the soundtracks interpreted the source material. Well, I haven’t seen the latest one yet, or listened to the music, I have no idea.

But of course I know the Howard Shore scores, and I think they’re fabulous. And a lot of people compare my music with Shore, but the difference is Shore wrote film music, you know, he underscored what’s on the screen. And I was writing music without a screen, and I tried to create the characters just through the music.

And I think I was successful in that, of portraying Gandalf in Hobbits and Gollum and all that, and later Galadriel. So my challenge was to bring those characters alive. But the reason I chose Lord of the Rings is for exactly that reason, that it’s such a colorful book with colorful persona and a lot of action, you know.

So it was a great choice to take Lord of the Rings as a subject. If I’d chosen something else or just Symphony No. 1, I don’t think I would be sitting here.

I don’t think it would be so popular. I mean, it’s certainly more than a marketing gimmick. I mean, you listen to the symphony and you can clearly see the action that’s happening in the book.

But I think you’re right. I think for a lot of people that’s what draws them in is that title. Yeah, it should trigger the curiosity of conductors and orchestras and all.

And if you look at my titles, I tried to keep them as short as possible, you know, like one-liners. And so The Red Tower, The Big Apple, Planet Earth, Return to Middle Earth. That’s a little longer, but that’s also based on Tolkien, Symphony No.

5, Aquarian. Well, look at my list. And yes, the title is super important.

It’s the trademark that’s on the score. If you just call it Symphony No. 1, it’s kind of boring.

That’s why I called T-Bone Concerto instead of Trombone Concerto, you know, a little pun to the bone, to T-Bone, and then movements being rare, medium, and well done. Yeah, that was a good one. Well, and I have to say, I’m somebody who has a very hard time picking favorites, but I can easily say that the T-Bone Concerto is my favorite piece of music that’s ever been written.

I mean, it’s just perfect in every way. So if you’re listening and you haven’t heard that concerto, I’ve spent many hours in high school trying to hack it. My brother and I want to know, though, how do you eat your steak? Medium.

You’re medium. Medium rare, medium, yeah. The second movement, yeah.

So anyway, yeah, T-Bone was my first solo work for the wind or brass instrument from 1995. I now have 10 solo pieces, so the T-Bone was the first one, and I’m happy to say it really became a standard piece on the trombone repertoire. All the big trombone players in the world have played it, you know? Joe Alessi, Christian Lindbergh, Alain Trudel, you name it, the whole list goes on.

Ian Bushfield, Ian Bushfield, Michiel Becker, and so on, Peter Steiner, and so on and so forth, which is fantastic. The same now happens with the UFO Concerto, you know, my UFO Concerto, also sort of a pun, that is now on the repertoire of a lot of UFO players and the big ones, you know? Robert Flaten, what’s his name? My friend Pepe Abbe in Japan, I was just emailing him this morning about it. Steve Meade recorded it, you know? So David Childs, of course.

So that’s great, and I’m very happy, very pleased and honored. I think one of the reasons it’s so special is it does so many things that people don’t realize the trombone can do. Of course, you know, having played it for so long.

I’m wondering if you see it that way, though, like when you’re composing a piece, are you trying to sort of intentionally push the boundaries, or are you just writing what you want to write, and it just happens that way? The latter, yeah. I’m not on purpose making it more difficult than necessary, you know? Not only for solo works, also for works in general, you know? I’m not very good in writing in grades, you know, like a grade two and a half. I’ve done a few successful or not successful, but I’m not an educational writer, you know? We have some people in the industry who are amazing at it, like Brian Balmages.

He knows so well how to write good music for younger bands, you know, and that’s very important. We need that literature as well, because that’s the material where people start to learn to play, you know? Those are our future players. I’m not in that category.

I’ve done a few easy works, like Aquarium and Los Cuatro Vientos, which is my first grade two and a half piece, and that turned out pretty well, but it doesn’t excite me, you know? Writing educational is not for me. I just want to write music, just whatever comes to my mind, you know, and also on a more higher artistic level. Now, one thing I have noticed is you have a lot of different orchestrations to your pieces.

You have the orchestra version, the small ensemble, the large ensemble, the concert band, and so on. Do you have thoughts on how to write something that will work with flexible instrumentation, especially in the band world, especially after COVID? There’s a lot of demand for pieces that will work with unusual combinations of instruments. Is that just your skill as an arranger, or is there something to wind ensemble, and specifically how it ties together? The flexible instrumentation, you know, is a great tool, especially, like you said, during COVID, you know? We needed music for small ensembles, but it’s basically a four- or a six-part piece, you know? Part one, part two, three, four.

And unfortunately, a lot of music is written that way, you know, with a lot of doublings, where the baritone sax and the bassoon and the bass clarinet and the euphonium all have the same. The horns and the saxes have the same. The trumpets and clarinets have a lot of doublings, so as a result, everything sounds the same.

And I don’t think I make that mistake. I orchestrate very specific, and that’s what I learned from the masters, you know? You don’t see a lot of doublings in orchestral scores. Well, sometimes, you know, between the violas and the clarinets and the bassoon and cello, but that’s just a color, and that’s how I write.

And talking about cellos, I write more and more… The bigger works all have cello parts now. Why? Because I just love it, you know? The sound, it adds so much to the foundation of the wind orchestra. So ideally, especially when I go to Japan, I always have four cellos and two double basses.

Last month, I had three double basses, and boy, it makes a difference. It really sounds much better, much richer, you know? And you can use techniques like pizzicato and all that. So to someone who’s not familiar with the world of concert bands or wind ensemble or whatever you want to call it, how would you explain that world to them? Who’s playing the music? What are the trends that are happening right now that you see in that world of literature? Well, unfortunately, in my 40-year career now, or almost 45, I still have to explain to people that a band is not, you know, a marching band or a hoompa-pa band.

There’s still a big misunderstanding on what a band is, and I never use the word band, you know? It’s a four-letter word. I always say wind orchestra, and that’s the best way to describe it because how many names do we have? Wind band, concert band, symphonic band, symphonic wind ensemble, symphonic winds, wind symphony, you know? Yeah. But it’s confusing.

A wind symphony, no. I would say in Dutch we say harmonieorkest, harmony orchestra, versus symphony orchestra. If you say wind symphony, there’s wind and symphony, you know? Wind orchestra says it all.

It’s symphony orchestra or string orchestra or wind orchestra. So I keep, and all my publications have wind orchestra or wind orchestra or brass band, you know? That’s very clear. But there are at least eight to ten names for the same instrumentation, you know, symphonic winds, a wind ensemble.

And, of course, there is a difference, like the Fred Fennell wind ensemble is one tool apart, you know, with no doublings, with three trumpets, three trombones, six clarinets at best. That’s something else than a large wind orchestra. Right.

So I would say, okay, you can call that a wind ensemble and wind orchestra. Those two differences I can make. But a wind ensemble could also be an octet, you know, or like the Dvořák with cello and bass.

So, yeah, wind orchestra, that’s easy. I wrote an article, which I’m happy to send to you, and you can send it to anybody else, together with Frank Ticheli, Alex Shapiro, some European composers. And the title is Trends and Changes in the Wind Orchestra Literature over the Last 25 Years.

And it’s a very interesting article. It describes how much has changed in orchestration, in presentation, locations, you know? People play more and more outside of the concert hall, in an old factory or things like that. And I love that.

So I will, after our talk, I’ll email it to you, and you can spread it, put it on your website. It’s public. Yeah, I’ll put it in the show notes for the episode, so when people listen, they can click on the link.

So everybody wrote a chapter. And it’s very interesting and very well done. You know, they really took it very serious.

Also, some conductors, like Eugene Corberon, wrote a nice chapter. And Oscar Navarro, my friend from Spain, who’s now very, very popular, especially in Europe. And my chapter describes my music in three categories, being the use of one of them is the use of rare or non-musical instruments, which I’ve done a lot, you know, using the bottles in Extreme Makeover and using funny percussion instruments or empty beer cans, you name it.

The other one is incorporating existing music, which could be folk music or classical music. Again, Extreme Makeover is an example where I use Tchaikovsky’s String Quartet, second movement, as the main theme. And the other one is using space, more than the podium, so offstage, backstage, from a balcony, you know, widening the performance space is one of the things I do a lot.

A good example is my saxophone concerto Fellini that uses a circus band and they’re in the lobby. And it’s always funny because it’s never the same. It’s a small ensemble.

It’s almost like soldiers’ tale instrumentation and with a bass drum and a sousaphone, a cornet, a clarinet, a piccolo, an accordion. It’s just a parody of a small circus band and they play a completely different role than what’s happening on the podium. If you look up on YouTube, Fellini, Jan de Meijer, you’ll find many great performances and it’s hilarious.

It’s a theatrical piece. The soloist is not the soloist who stands next to the conductor. No, he’s all over the place.

He starts behind a makeup table on the podium while the orchestra plays the introduction and he starts to put on some makeup with one hand, a little red nose, and with the other hand, with his left hand, he already plays a couple of notes on the saxophone predicting what’s coming next. And then suddenly the circus band starts to play a march in the lobby. And he wakes up because he’s dreaming.

He’s the clown of the circus. He has to do the show four times a day. He hates it.

He hates his job. He hates his life. That’s sort of the typical cliche clown story, you know? Because Fellini, the filmmaker, used a lot of clowns and circus in his films.

So when the circus band starts to play, the soloist sort of wakes up and thinks, oh God, and he leaves the podium and walks to the circus band and joins them to play. And then he comes back from the other side and lands on the sofa. Anyway, watch it on YouTube and I think you’ll enjoy it.

Yeah, we’ll link to that as well. I wanted to ask you, when a composer has a successful premiere or maybe they win a competition or they have a moment of success, what’s important for them to do to make sure that they don’t miss the moment? How do they capitalize on that? Well, of course, social media nowadays is very important. If you make a nice press release, if you win a prize, that’s what I do.

I put it on social media and everybody sees it. You need a good website, of course, and a Facebook page. And right now I’m doing Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter, and three Facebook pages, three different ones.

With that, I reach almost everybody. Are you doing it all yourself or do you have a team? Yes, I do. No, no, no.

The social media, I just do myself. Just on my phone, you know, I make a message and a photo and boom. So how on earth do you manage your social media, write new music, and travel all over the world conducting at the same time? I mean, literally, how do you remember your own name? That sounds like so overwhelming.

What was my name again? Sorry. Well, yeah, I have a lot of energy, thank God. And I don’t do jet lag, you know.

I travel a lot internationally. When I arrive in Japan at 3.30 in the afternoon, I say to myself, okay, it’s 3.30 in the afternoon. Don’t think about what time it is in New York.

It’s not going to help you. Just stay up, you know, have a meal, go to bed at 10, take some melatonin. Next morning at 8 o’clock, I’m fine.

And coming back, same thing. But, yeah, it’s sometimes difficult, you know. I’ve been traveling since September almost constantly, and I haven’t written a lot of music.

Just some arranging and a lot of editing. I just finished a big revision on Lord of the Rings after 35 years. I redid the whole score.

It will come out April 1st. And I changed a lot of the instrumentation. I took out all the repeats.

I wrote them out because, you know, the second ending, first ending, it’s always confusing, especially at rehearsals, you know, when you say, okay, let’s do 35 second time. Well, forget it. Half of the orchestra goes back and repeats, you know.

Or second time only or first time touch. So my advice is don’t write repeats. It’s confusing.

Just write it out. It costs a little more paper, but then you won’t have those accidents with people don’t understanding. And you can make the second time different.

For instance, in Lord of the Rings, the chorale, you know, in the middle, it used to be a repeat. And then the second time, now it’s all written out. And no mistakes.

No people playing the first time instead of the second time, et cetera. So I also changed a lot of instrumentation in Gollum, the third movement. You know, the tricky 38.

I all moved it to harp and piano and mallets instead of the winds, because that always went wrong. It has been irritating me for 35 years. So I said, okay, I’m going to rewrite it.

It was just not well orchestrated. I had wondered about that because you said it was your first piece and then you’ve composed so much since then. And I wondered how you can stand conducting it for 35 years without rewriting it constantly.

I mean, that’s what I would do. Well, that’s what I’ve been doing over the last… I mean, I’ve conducted the piece hundreds of times and every time it was, okay, let’s move this here. A trumpet key plays an octave higher.

A timpani, you know, hundreds of comments. And that costs so much rehearsal time. And then I said, you know what? I’m going to publish a new edition.

And I’m probably destroying the stock that we have from as soon as everything is available, then I’ll just have the old stock removed. So people can only buy the new version. Do you have a favorite moment in the piece? Several.

Yeah, I enjoyed the Hobbit’s hymn. You know, it’s beautiful. I was going to say, actually, I was doing some listening on YouTube and it looked like you were having the most fun conducting that part of the piece.

Yes, it’s emotional for me because the hymn was played at both my father and my mother’s funeral. So for me, it has a different impact now, you know? And it has nothing to do with the book. No, I think about my parents when I conducted it, you know? Have you put words to it? Some people did, yeah.

What was it? In Germany, somebody, with my permission, wrote a hymn. And there’s some school in the US who adopted it as their school hymn with words, but I forgot where it was and what the words were. What is your process for composing? Do you start with melodies? Do you start with a structure? How do you approach it, especially with a large work like that? I have no recipe.

I usually start with the title. And the form, you know, is it solo concerto, is it symphony, is it overture, whatever. But I have no… I never do the same thing.

Sometimes I start in the middle. Sometimes I start beginning. Sometimes I start just finding new chords, chord progressions, or I find a melody and I put chords to it.

One of the reasons I don’t teach composing because I don’t know how to explain it, you know? It’s such a crazy process that happens in your head. And sometimes people ask me, what program do you use to compose? And then I say, oh, is there one? I mean, I’m using Sibelius, but that’s notation. That’s not composing.

That’s something different, you know? Right. What do you use, by the way? Finale. Finale, okay, yeah.

No, I use Sibelius, and thank God there’s Note Performer, which I recommend to everybody, especially young composers, because don’t use the general MIDI. It’s horrible. It’s absolutely horrible.

It sounds like a barrel organ, you know? And Note Performer is a great program. It sounds really like real instruments. And I know the guy who developed it in Sweden.

His name is Arne Wallander, and I am in touch with him if I have a little problem, you know? He responds immediately. So I highly recommend using Note Performer. I think you can also use it with Finale.

Because I don’t think the general MIDI of Finale is much better than Sibelius. My advice for young composers, if you send in a piece for a competition, don’t send in the general MIDI, because you disqualify yourself immediately. I cannot listen to it.

It’s so terrible. We recently had this discussion with the ABA. I’m on the jury of the ABA, Oswald, you know, the American Masters Association, which is taking place right now in Lawrence, Kansas.

But I couldn’t go, unfortunately. But we had this discussion, should we accept only live performances, recordings, or MIDI? And I said, well, my standpoint was MIDI, but please use the right programs. And of course, live is our preference.

Because that’s what real people… If you have a good MIDI program, you can make the most impossible technical things possible. Because, you know, the computer reads it. So we had a big discussion, a very interesting discussion about it.

So my advice, composers, if you send in, and it has to be anonymous, you know, you can’t put your name on, but make sure you have a good MIDI recording. Otherwise, you have no chance. So let’s dig into that a little more.

How important are these composition contests to new composers starting out? And what would your approach be for deciding where to submit and how much emphasis to put on it? And like you said, you yourself are still submitting for contests and winning awards. And so how are we supposed to compete with you, you know? Well, I’ve lost many times. I’ve won like 8 or 10… I don’t know the number, it’s on my website.

I’ve won 8 or 10 major compositions contests. Like The Settler was the big one, The Lord of the Rings. And in Corciano in Italy, I’ve won like 4 times.

But it’s all anonymous. So, you know, nobody knows who’s who. Casanova won there, Planet Earth, Echoes of San Marco.

It’s super important. I mean, if you… we talked about this earlier, you know, PR, if you want to put your name on the map, winning a prize is fantastic because then you can tell the world, you know, and people will be interested in the piece and it will get played and you can put it on the score. So I always look out for competitions.

The problem is that most of the time it has to be unperformed and unpublished. And of course, all my work gets published and performed. So I can only send something in if it’s before the premiere date.

And sometimes I just change the name. I change the title on purpose. I just give it a motto to hide the identity of the composer.

Are you still self-publishing your music? Yeah. Amsterdam Music is my company. I work for several freelancers.

The most important was Tom Zichterman. He’s also a composer from Holland. He’s my main editor and I’m in contact with him every day.

He makes the final edits, you know. He designs the scores and we do everything together. He’s fantastic to work with.

And Hal Lennart is my worldwide distributor. That started in 1995. So the first seven years I did everything myself out of my basement in Amsterdam, when I was still living in Amsterdam.

In 2000, I went with Hal Lennart. USA was for US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand. And then in 2000, I signed a contract with De Haaske, then with Jan de Haan, for the rest of the world.

In 2012, I think, De Haaske was bought by Hal Lennart. So now, which was very convenient for me, because now I have only one agency, one publisher who sells the music they printed too. My music gets printed either in Winona, Minnesota, or in Holland, in Heerenveen, where the old De Haaske company is still based, but now it’s called Hal Lennart.

How has that process changed over the last 35 years? And what have you found to be the most successful in terms of marketing your own music? The most important change is that we now only print on demand. So, beginning until 20 years ago or 15 years ago, we would print 100 copies, you know? 100 sets and 125 scores. Nowadays, we start with 25, and when they’re sold, we print another 10 on demand.

So, that’s much better. Less stock, less inventory, less initial costs. So, that’s the most important change, I think.

And of course, the software has become so much better. Another reason I wanted to redo the Lord of the Rings is because the score is terrible. The old score is made in Composure, which later became Finale.

But if you look closely to the original Lord of the Rings score, all the grace notes, all the crescendos, all the slurs are done by hand because you couldn’t do them in Composure. It looked terrible. So, there’s a lot of, I mean, thousands of little things or accents I’ve done on original sheets, and then we printed from there, and now it’s all cleaned up, it looks much nicer, and it also sounds better.

I did it in Nagoya last month for the first time, the new version, and it sounds more transparent, and it’s easier to play because it’s easier to read. So, that was a good decision, I think. What advice would you have for composers that have received a commission? Advice for negotiating your fees and communicating with the conductor and all of those sorts of behind-the-scenes details? That’s hard.

Every time it’s different. Most of the time there’s a budget. They say, okay, we have $8,000, and can you write a 12-minute piece? Something like that.

When I get a request for a commission, I have just a small sheet. I have a minute price, so $70 per minute with a minimum of five minutes and all that. But I’m also open to, okay, what’s your budget? I’m not going to count minutes.

I just say, okay, for $7,000 I will write this piece for you, and no matter how long it will be, that’s what I do most of the time. Well, I really appreciate you taking the time to talk to me. One final question.

If you could go back and talk to yourself 35 years ago, what would you say? Oh, my God. This is a good question. The May? Go for it.

Follow your heart. That’s my advice to all people listening right now, composers, conductors. Follow your heart.

Dream your dreams and go for the impossible. Believe in yourself and just write beautiful music. That’s perfect.

Thank you again for taking the time to talk to me. It was a pleasure, Jared, and I hope to meet you very soon in person.