Ep. 23: Navigating the New Music Industry with Philip Keveren

Episode Description:

Master composer and pianist Phillip Keveren joins me on the podcast today to talk about how the music industry has changed and how composers can success by diversifying. We also break down how to write succesfully for the piano, church, and educational markets.

Featured On This Episode:

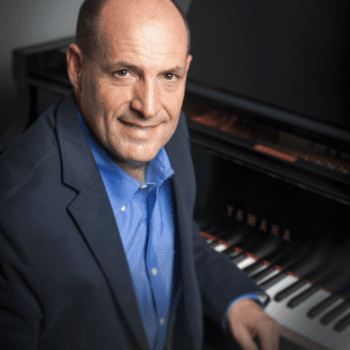

Philip Keveren

Garrett Breeze is a Nashville-based composer, arranger, publisher, and the founder of Selling Sheet Music. His credits include film, television, video games, Broadway stars, major classical artists, and many of the top school music programs in the U.S. Visit garrettbreeze.com for more information or to book Garrett for a commission or other event.

Episode Transcript:

*Episode transcripts are provided by Apple Podcasts and have NOT been proofread.*

My guest today is pianist and fellow Nashville composer, Philip Kevrin.

He is the co-author of Hal Leonard’s Student Piano Library Method, as well as hundreds of published arrangements for solo piano. He has written extensively for the church music market, including arrangements for major Christian artists such as Steve Green, Travis Cottrell, Larnell Harris, Sandy Patti, Mandeza, Jeremy Camp, and the Brooklyn Tabernacle Choir. We had a great conversation about piano, Spotify, how to write educational music, and the many ways the industry has changed over the last 50 years.

And at the end of the episode, I share recordings of two of his recent works. Philip Kevrin, welcome to the podcast. How are you doing? I’m good.

Thank you, Garrett. Thanks for having me. So to kick things off, I knew of you first as a church musician, and then afterwards I sort of discovered all the piano methods and the arrangements and everything else.

And so I’m wondering how much do you think for marketing purposes or even musical purposes, like how important is it to put yourself in a box as a composer, to be known as I’m a church musician or I’m an arranger or I do educational music? How much do you think that distinction matters? It seems like the more you try to control that, the less you can control it. I have just always kind of worked in whatever came along and those streams opened up and then people put you in the boxes. It’s always been kind of a strange thing to try to understand, because I’ll get some people will come at me from the secular world and be surprised to see the sacred side of things and vice versa.

And I don’t know. It seems like people will create a box for you and put you in there. And I’m happy to write in whichever box I end up in.

I mean, I think it’s useful to a certain extent. Like, you know who to market to if a lot of your music is for a specific thing. But sometimes I’ll find myself with an idea for a cool arrangement and I’ll kind of second guess whether or not I should even do it.

It’s like, well, people know me as a show choir guy, so should I also try and arrange something a cappella or are they just going to blow it off? Because that’s not what they expect from me, you know? Yeah. I understand what you’re saying. I’ve just kind of gone and thrown things against the wall and let them fall.

And what’s really interesting is that I did an arrangement years and years ago of Still, Still, Still, the Christmas Carol for choir, but it ended up in the educational market. And the educational market, completely separate, as you well know, from the sacred choral market. And all of a sudden I was getting all these notes and things from school teachers.

I’m going, what? I mean, I didn’t really realize that that’s where it was going. And so, you know, there are these illusions. And then there are also these walls.

I guess Christmas music kind of jumps over the wall, doesn’t it? Seems like it kind of exists in multiple paradigms. Do you think those walls are changing now that self-publishing is growing so much? I think it is. Absolutely.

Yeah. That’s really true because people go to a site for a composer, someone with whom they have a relationship from whatever direction, and then they kind of find the things that are part of their world. So what has your experience been with publishing? Because I know you’ve done it both ways.

You have hundreds and hundreds of things with Hal Leonard, but you’ve also published on your own, and I’m sure there’s other publishers you worked with as well. Well, when I started, there really wasn’t a self-publishing road that I could see. You know, it was kind of, you went out and looked for publishers for things you were going to do.

And as time has gone by, you know, that has become an option here in the last season of my career. And I’m having fun exploring that direction. Traditional publishing has been good to me, but it’s also, you know, its perils are that the publisher puts you in a box and says, this is what we want from you.

And when you stray a little bit one way or the other, they’re reining you in for what, you know, how they want to market you. So it’s fun in the self-publishing direction to just kind of write for things that you see as chances to explore different things and find out where it might go, you know? Yeah. What are the things that I’ve worked the best for you with marketing your music? Well, I have so little experience marketing my own, you know, from my own website.

I’m truly learning that as we speak. I know that from the traditional publishing side, the thing that really always seemed to be at the center of a piece or a certain direction working was some key person or institution that used or recorded or, you know, and then that, and then it grew from that. Was that typically somebody who commissioned a work or was that just, uh, luck? I suppose.

I think there’s, I think luck. Yes. And also, um, I did, I’ll tell you what I did do earlier in my career is when I, even in the, in the traditional publishing route, when I would finish something that I thought had merit for someone, I would send things to people.

Uh, I had a connection for, you know, Brooke May’s piano in Dallas, which was a force in its day. And I would send it to their person that stocked that store and say, what do you think? You know, is this something get, I kind of learned that it was smart to get to know the key people in those big print stores. Uh, that’s an era gone by, you know, that just doesn’t really exist at this point, but it sure was true 25, 30, 40.

Well, not 40, 30 years ago. Those were really important people to get to know and send stuff to. So who would you say are the equivalent people now, now that everything’s digital? Oh boy.

Um, you know, there are all these bloggers and podcasters you ever heard of these podcasts for people. I, I, I think that’s, that’s kind of where it is now. I mean, I recently did an interview with someone who out of nowhere says, Hey, I found your, your jazz book for it’s, what is it called? Bach is awful, but I can’t remember it.

They are box pieces that I arranged for jazz piano. And this person found the book. I did an interview with this podcaster.

And then next thing I know, I’m getting a call from someone who is playing this in a club in Minneapolis. And they discovered this book from this podcast. And then they’re playing from this book in a club atmosphere where there are people that play piano.

And then it grows out of that and you realize, Oh, okay. Those sorts of things are important to do as in podcasts. Well, thank you for the flattery.

I do think though. Um, well, okay. The stores are gone, but there’s so much more competition now that I think there still has to be.

Well, how do I want to put this? There are still going to be key players in distribution and marketing and, and just helping people filter through all this stuff. I mean, that’s the challenge now, right? Is if you are a self-publishing piano arranger, you know, how many thousands of piano arrangements are you competing against and how do you figure out how to get the word out? Yeah. And it’s interesting.

You know, I put an ad in piano magazine in their spring issue, a magazine that has reviewed my piano works for many, many years. And I just put an ad in there and said, Hey, guess what? I’m going to be doing stuff at my own website as well. Thinking, does anyone even look at advertisements in this magazine? I don’t know.

And jury’s still out on that, whether that was worth, cause it wasn’t cheap to do, but I thought, well, you know, let’s give it a run and see whether it is worth, you know, the old thing of the, where do you advertise? How much? Well, I guess what I’m, I guess what I’m really asking is, is what, what do you think has changed? And what do you think hasn’t changed? Because so much of it has gone digital, but a lot of the key players are still the same. And a lot of the ways people at least perform the music are still the same. So surely there’s some similarities.

There are, you know, tastemakers and influencers. They’re just not at a, a dealership or a print store. They’re, you know, now a podcaster or a, you know, at a university setting or, but it is really talk about early in the internet days.

I remember guys saying to me, you don’t want to be a hot dog stand in the desert. And I always thought that was a great, yes, you can build a hot dog stand in the desert, but does anybody know that you’re there, you know, and with my own website, I didn’t want to be a hot dog stand in the desert. You know, I have the, the advantage of a network of people that know my work through traditional publishing.

So I, you know, it gives me a little leg up with marketing from that spot, but yeah, I mean, this, this very same discussion can be had exactly for the recording industry. It’s, you know, you’ve got Spotify and 10 gazillion people putting their stuff up there. And okay, do you need a label to be marketing your music or can you do it yourself? But if you do it yourself, then how do you get the attention of the people putting together playlists? And, you know, is it worth paying somebody $1,500? Let’s say so supposed playlist promoter.

Is it worth it? You know, I, I don’t know. well, let’s go there because one of the things I wanted to talk to you about is how much you have recorded your music and put albums of your music out on streamers. And I counted before we got on here, I counted 50 albums on Spotify.

And I think that’s one of the things that composers really struggle with is getting recordings of the music. And obviously when you play piano yourself, it’s, it’s somewhat easier to record piano albums, but, but they’re not all just piano albums. I mean, you’ve got orchestrations on there, you’ve got full orchestra, you’ve got instrumental things, you know? So I guess, talk me through your strategy in that and how it all came to be and, and what do you think has worked and, and hasn’t worked? Well, the vast majority of those recordings are things that were done in the CD era and have then migrated into streaming.

However, over the last five or six years, I’ve done a lot of things for Burton Avenue Music and Green Hill and, and those folks that are, that have really, you know, are doing well with the streaming paradigm. And I also went and recaptured some things that were recorded years ago that were no longer in print. And I just thought, you know, you always hear about, you’ll never get a publishing company or a record company to, to release the master back to you, you know? Even if you can put a price to it.

No, they own it. even if they’re not putting it out, you’re not going to get it. But I, that’s not what happened.

I went to a record label and said, Hey, you have stuff that’s not out there anymore. What can I do to get those masters back? And we worked it out and I’ve re-released four or five of those things that in their day had, you know, really good budgets for piano and orchestra. And now they’re back out in streaming.

So you pulled a Taylor Swift? I did. Sort of. Yeah.

I’ve had bad luck or no luck at all getting things back. And then, and like I say, in this one case, they were very, very kind about it. Kind of said, you know, it’s silly for it to be sitting in our warehouse, you know? But the thing I don’t understand, Garrett, and I really don’t know the answer to this is that.

So I’ve had things with these different labels and then I’m doing things myself as well and releasing them. And then I, you know, I did a choral album with a couple other people and then it went up. You’ve got all these things getting uploaded from different sites and you put something up there and it has a window of about three weeks before the next thing comes along and knocks it down one in your release schedule.

And then, and then I get a call from someone, Hey, well, we didn’t know that was, you know, gosh, we were releasing your piano record on this is such a day. And two days ago, this thing appeared and well, I don’t, you can’t control all those entities. They all end up in the very same channel.

And then you end up with this over release problem. So, you know, that’s kind of a, well, I think you’re, well, I think you’re right. I think, I think the challenges of recording music and self publishing are very, very comparable because you have the same question on the, on the arranging side too, or the publishing side, you know, how, how often do I release new music? How much do I release new music? And, and I think the juries may be still out on that, but I do think there’s something to be said for, I don’t know.

There’s, if you, if you put out too much stuff, people get oversaturated and they just can’t handle it all. But if you don’t put out enough, then you get lost. Right.

And for the most part, I have never stressed one way or another about it. I just write. And then sometimes it gets bottled up and I’ve done too much.

And other times there’s a follow period, you know, but then it’s really weird. All of a sudden, a bunch of stuff will come out that was done at totally different times, but they just got together and out. They come and people go, do you ever sleep? Well, actually, yeah, I slept for a long time.

It’s just, I did this two years ago. Yeah. Yeah.

I forgotten. I did it at this point. So how do you manage all your different projects? I think, I think the time management and the project management, I think that’s something a lot of people struggle with.

When you have multiple, multiple projects for different clients, you have your own stuff, you have, you know, the recorded and the sheet music, and you’re trying to market it yourself and you’re trying to wear all these hats. How do you personally juggle everything and keep track of everything? That is the, the aspect of freelancing, entrepreneurial freelancing that I’ve always loved. That’s the thing that I enjoy having.

I mean, I just have the big board up on the wall and I’ve got a timeline with everything. And I walk in my room first thing in the morning and I look at it and see what I need to do to bring each one of those things to the next spot. And if I don’t see it personally, my way, my mind works.

If I don’t see it up in an analog form on the wall where I can chart it and keep track of it, I lose control of it. But that’s the way I, I have functioned and I have dropped the ball a few times, big time where I miscalculated and suddenly found myself in need of a ghost writer. Although I’ve never actually, I don’t personally believe in ghosts.

I was co-arranger or co whatever. I’ve always credited people when I’ve done that. But yeah, that’s kind of how I function.

So I like doing that. And then I never stick to it. That’s a personal failing of mine, but it always seems like there’s something else that comes up.

You know, you get, you get a clear set of, of deadlines where I want to put this out here and this out here. And then, then, you know, so-and-so comes up with a studio session that’s tomorrow and you have to drop everything and do that. And then you just get this domino effect of everything just kind of falls apart.

Yeah. That happens to me too. And then you regroup and, and get back on target with whatever it is.

I spent the entire day yesterday recording a piano solos that I had intended to do a month ago. And that created a real mess for me because I have to practice. I’m not someone that walks in the room and just, so I had all this stuff really prepared.

It was nine solos that were difficult things for me to keep under my fingers, had them ready and then couldn’t do the session. And so for the last month, I’ve been trying to keep those things under my fingers while I’m on doing other things. And I was not a pleasant person.

The last week I was, my wife would tell you I was grumpy because I had had it trying to keep those things practiced and prepared to be recorded. I recorded them yesterday and I am a happy camper today because they are done and off my plate. So I’ve heard a lot of people talking about this idea of, you know, you sort of do things in batches, right? You know, you, you write 10 songs or you record 10 songs and then, and then you sort of schedule them out.

So it’s like, you’re going to do one a month. And then you know, you have stuff coming down the line and you kind of get a bit of a breather. Is that how you operate or do things pretty much just go out the door once you have them finished? Yes, both.

But I try as much as possible. And I say, Triger is at the front side of a project before you’re into it. And expectations are set with the people that you’re working with to be as clear about what’s ahead as possible.

What is it that you want from me? When are you going to want it from me? And I’m always very, very raised eyebrow when someone says to me, there is not a deadline for this project. We just want you to be creative. And it says.

You, you have a deadline in mind. You, you have an idea of when you’d like to do this. You’re just not telling me right now.

You’re not telling me what you’re really thinking. And I dig, dig in on that. Oh, no.

What no, you have a deadline. When are you going to want the first one? Because I hate that feeling to be into something. And then you get the call.

So how’s that coming? Yeah. We’re talking about a session in two weeks in. So with sheet music in particular, how much have you noticed the timing making a difference? Does it really matter when you put these things out or.

Is it just a question of when it’s going to catch the cycle? I don’t think it makes that big a difference, honestly. I mean, Christmas, you know, I’ve been writing Christmas material in April and may for the last. Gazillion years and they want it done so they can have it.

You know, ready to come out in the fall, whatever. But what I find normally. Frequently, at least with piano music, I can’t say.

I’m not sure that’s necessarily true. With coral things, but definitely with piano music. It doesn’t find its home until the next season.

It comes out and it ends up sitting there and gets found next year anyway. So I’m not sure that that deadline made a lot. When it comes to educational piano music, it used to be.

If you didn’t have your book out, your thing out for, you know, MTA, Music Teachers National Association, it was not going to, you know, it was going to be followed for a year. But that’s not true anymore either. OK, so I’ve always just assumed that.

Piano music does. Better with digital sales than other types of music, you know, choral is still very much a print thing because no no choral director wants to go, you know, print and staple 100 copies of their music. But when you have a single piano player, I mean, does that does that match with what you’re seeing? What I’m seeing is that the core method books in a piano series are going to still be a print thing.

They want the book. But when you’re talking about an arrangement or a piece that that’s in a collection, let’s say I do a collection of spirituals for intermediate piano, I’m seeing more and more that go where they’ll go pick the arrangement they like and buy it digitally as a single. But but like I say, method books still very much print oriented.

So these piano collections, do you think they sell better because they’re in a group? Like, do you think releasing one a month would do differently than putting them out in a big batch like that? Do you think there’s something about having them grouped together that makes a difference? Because as you said, people are buying them individually. But do you think that do you think the fact that they’re part of a package helps? I think it does, because they’re drawn to it initially as, oh, I’d like to have something of this ilk. And then they look at it and they pick out their favorite.

And, you know, I think there’s even a certain amount of, you know, they go online and look at the book and kind of see the general level of it from the website and then pick out the title they like. But, you know, they’re still buying books, too. But I don’t know what the ratio is anymore.

Yeah. When it comes to extracurricular folios, I’m not sure. Well, let’s get into piano then, because I can’t have you on the podcast and not pick your brain on piano.

What advice would you give to somebody writing for piano for whom that is not their primary instrument, which I think is most composers or arrangers? You know, piano is one of those instruments that everyone is asked to write for at some point. Yeah. It’s interesting.

Some of the very, very best piano and certainly successful piano arrangers that I can think of knowing in my career, piano was not their primary instrument. And as a result, they approached it with trepidation and great care as to making it really playable at a global level. There was a guy named Bill Boyd that wrote easy piano type level jazz pieces.

He was a jazz band guy. He taught band in college or high school. And then he started writing piano arrangements sometime later in his career.

And when I first started in the late 80s, he was kind of the guy for piano jazz. And I was so surprised when I met him and talked to him. He’s like, yeah, no, I don’t really play piano.

But he’d go to the middle of the piano, and he knew how to voice things well and simply. And if he could play it, he knew that it could be taught. And that was fascinating to me.

Sometimes piano players that have a lot of facility overestimate the average wannabe amateur pianist and create things that they may be pianistic and they may be playable, but they’re playable at too high of a level. And my best selling books always have been more to that intermediate level. Even advanced pianists will say, oh, I wish you would write stuff that’s harder.

I really want an advanced book. And then you do a really advanced book, and it sells one quarter of what that same title list did at an intermediate to upper intermediate level. I think advanced pianists like to buy books that they can sight read, and then they add things to them.

When you give them something really difficult, they look at it and go, eh, I don’t want to practice that hard. So how do you determine what the difficulty level is of a piano piece? I was a band kid, so I know there’s grade one, grade two, grade three, all the way up. And there’s very specific things.

If you have this number of key changes or even this number of flats in the key signature, that puts it into this level. I mean, what are the things that you look at to determine the difficulty level of piano? Piano has never been that graded specifically in this country. It has been more per publisher.

You go and you look at Alfred’s materials, and you look at it and figure out kind of how they’re grading things. You go and look at the Bastion materials and get a sense about it. You look at Hal Leonard’s.

You kind of have to look and see how they’re plotting things. I got to know the Hal Leonard spectrum of that because I was part of writing that method in the early 90s. And it’s very, very specific within the structure of that piano method.

But when I do books, my series of books that have my name on it for Hal Leonard, I was working with their head level called Beginning Piano Solo, and then Big Note, and then Easy Piano, and then Piano Solo. And I kind of worked it out in my own mind within each of those levels more or less. But you’re touching upon something.

In the Royal Academy of Music and the Australian music system, there are places primarily in British flag countries that have really, really carefully graded systems. And I’ve never written for those markets. The U.S. market is not as clearly annotated as that.

But within my own series, people know when they go to it, they know what my Easy Piano basic structures are. But it’s not what you mentioned like for your band stuff. It’s never been that clear in the piano markets.

Well, and I just wonder because when you self-publish something, they always ask, what’s the difficulty level? And it’s usually like beginner, easy, medium, hard, advanced, maybe an intermediate-advanced. And sometimes I wonder if I’m checking the wrong box because I don’t really know. It’s not clearly defined.

And for some people, that probably matters a lot, that they’re not even – if they’re filtering by only intermediate, they’re only going to see those. And so it feels like a shot in the dark almost with some of this stuff. It is, even for the publisher.

We will go back and forth. When I send in a book, I’d send it in and say it was lower intermediate, and then my editor would come back and say, no, we’re going to call it intermediate. Say, okay, based on what? Well, just kind of think, you know.

And the other thing about it is people judge, in my opinion, quite often judge the thing that makes a piano piece. They judge the wrong things into what makes it difficult. You can have scale patterns going all over the place that look difficult.

They’re actually easy. And something that is harmonically complex may not be technically difficult, but it’s harmonically sophisticated. And you’ve taken something from what maybe you could say, oh, that’s an early elementary or late elementary or early intermediate piece technically.

And I would say it’s an advanced piece. You give this to a younger student, they will never play this well. And it should not be something that’s given to them at that level with the expectation they can be.

It’s an advanced piece. So you’re saying look at the technical difficulty, but also just the compositional difficulty of it. Yes.

You know, something that has colorful harmonies in it that are not, that someone with not a lot of experience will think they’re playing wrong notes, you know. And you’d be, gosh, you should see. I get emails sometimes that disfloor me, you know.

A piano teacher that is very much a classically oriented person who has mostly younger students, and their whole world is very diatonic. And they buy something of yours that has some jazz colorings in it because they know my work from pedagogical material. And they’ll send me notes.

Is measure eight, you know, you have an A in the left hand and there’s a G in the right hand, you know. Which one is correct? Oh, well, they’re both correct. All right.

Well, this may be an obvious question, but I’m going to ask it anyway. How is writing accompaniment parts different than writing solo piano parts? The teacher accompaniment, so to speak. Are you talking about for a piano piece that has an accompaniment for the student to play with? Is that what you’re talking about? Or you’re talking about for a singer or something? Well, yeah.

Let’s say you’re writing like a piano part to go with a choir arrangement. The piano is not the focus. Do you write that differently than if it was a piano solo? I mean, obviously, whether or not there’s a melody, you know, putting that aside.

Do you approach it differently? Or is that one of those questions that can’t be answered because it depends on the piece? I write as clear and not as – I’ll tell you this, Garrett. When I write piano parts, I almost always simplify. I write, and then I simplify, and then I simplify again because a choir accompanist wants to successfully undergird that choir, but they don’t practice enough.

I also bring them in range-wise. I’m pretty careful not to go too extreme in either direction. That’s where you end up with people hitting wrong notes.

So if you can keep them within a fairly tight geography in the center of the keyboard. I will say that when I’m writing for, say, a choral accompaniment, I don’t fuss around nearly as much with finger numbers and that kind of thing. But because of that, I think I end up writing a little simpler because I don’t want them having to work out some intricate.

One thing I do have learned to do over the years is make sure that that piano accompaniment, when it’s choral or a solo singer, either one, is handing pitches to people in the choir at key spots. So writing the accompaniment and then going back and looking carefully, okay, if I’m the tenor singing along with this piano accompaniment and I find it hard to hit such and such a note, I’d sure like to see that get interpolated into that piano part as much as possible. I also wonder, I’ve seen a lot of instrumental arrangements where the solo part may be pretty easy and then the piano part’s actually a lot harder.

It’s true. I mean, can we say Hindemith? That’s exactly who I was thinking of. The Hindemith trombone concerto is just a beast.

All of those sonatas are horrible for the piano. And I got to be a pretty good Hindemith faker. It’s like, find the rhythm and keep moving because you can at least keep the soloist from falling apart.

Yes, those parts are hard. I mean, I guess what I’m getting at is how much do you think the difficulty level of the accompaniment factors into whether or not someone buys a piece? Because a lot of times I think they’re focused on whatever the solo part is or the choral parts and maybe don’t look as closely at that side of things. Or maybe it’s a selling point.

Maybe it’s like you want your student to feel great and so their part’s easy, but then the piano is just going off. And is there a way to classify that? Because when you are publishing, let’s say it’s a Lizzo arrangement, flute and piano, right? The publisher is going to ask, what’s the difficulty level? And if one’s easy and the other one’s advanced, how do you relate that to the purchaser? Right, yeah. So I think the piano part is generally easier than harder.

You know, I will say this. You know what’s interesting to me on that subject is, you know, I played some of your piano parts recently for you and recorded them for your sessions. And you tell me you’re not a piano player, but your piano parts, even though sometimes you notated them in a way that is not my, wouldn’t have been my first choice as a piano player to see them, your logic of how they’re to be played, and they’re so logical that it was understood, I knew your intent.

So they’re very playable. And I say the same thing. Do you know Robert Sterling’s work at all? Oral? Yeah.

I wrote for years for Word. He doesn’t play piano at all, but his piano parts are completely logical. And, again, sometimes I look at it and go, I think this is what he means, what he’s, it’s not notated how maybe I would have typically seen it for piano, but so logical and playable.

My rule of thumb is if I can sort of halfway fake it, then someone who actually knows what they’re doing will be fine. I think that’s a great rule. And that’s the same rule I used for myself on so-called, when I have a book that says so-called advanced, what that means to me is that I can sit down and without practicing it, sell it at the piano.

Then that means somebody that thinks they want an advanced arrangement is going to be able to learn it. And a, you know, a professional pianist will be able to make use of it quickly. And that’s advanced.

Anything beyond that in the arranging world, you’re kidding yourself. It just will never be played well. Yeah.

So I suspect there are some people listening to this that either have created or want to create their own educational methods, either for their own piano studio or for some other, you know, just, just for Mark, just, just because they enjoy writing educational music. What advice would you have on how to do that, to create a series of music that’ll take a student from point A to point D or wherever you’re going Z, I guess is the end of the alphabet. The best educational piano music is, is written by someone that is teaching.

And if they’re not teaching, they need to be very closely aligned with someone who is because the last word in whether a piece is going to work for a student is the student. And I’ve always relied on teachers and students. You know, I run it through that, that filter when it’s going to be an educational release.

I was fortunate when we were writing the how Leonard piano method, my kids were student level. They were ages. They started playing that stuff when they were like six and four.

And so I was able to hear them, you know, practice that stuff. And I learned any pigs, they were Guinea pigs. And that was really helpful.

And, and what’s interesting, then we all that stuff, I guess to be more specific to your question is make sure that you have either taught the piece yourself or had someone teach it before you claim to be putting out a piano method. Yeah. So getting a little bit into church music, I think that’s one area where self-published music is doing quite well.

Do you approach that differently when you’re writing church music? I mean, I assume obviously the marketing is different because you’re targeting a more specific group of people, but do you write it differently or is, is it the same musically? It just happens to be material that a certain group is going to find more appealing. Yeah. I, I guess I sort of have my, my approach to music in general and I apply it to the church market, but at this stage of my life, I am writing very little music that’s being published in the choral church market.

That’s really just been post COVID. That’s just the way it’s happened for me. And yet I’ve done, I’m probably doing five or six commissions a year.

So I kind of always have a choral commission going here writing for someone. So in those instances, I find I’m writing different than I used to write for generic publishing like, because I’m sort of, all right, tell me about your choir. Yeah.

How is it going to be used? And I’m being a little more, I guess I’m to some extent I’m, I’m finding that to be fun to be a little outside of the box. Cause I know what, how it’s going to be used specifically. Now what I’ve not tried yet, I have not taken any of my commissions and put them on my site as things.

I, and I, do you do that? Do you, do you sell your commission works on your site? Oh yeah. Yeah. I’ve done that yet.

Yeah. I mean, typically there’s, you know, some sort of agreement. They get the first performance or they get it for X number of months and then it’s fair game.

You know, I’ve just never, I’ve never, and I, you know, that’s a project in itself, back through my stuff and getting that commissions up on my site. I haven’t, I haven’t done that yet. I, I probably know the answer to this, but I think choral is self-explanatory when it comes to the church market because churches have choirs or a lot of them do.

Do you think there’s a, what’s the, what’s the market for piano music in church? Like would you say, or in, or instrumental music, maybe. What I find surprising and it has always surprised me is there seems to be an unlimited market for traditional hymn piano solos. I just don’t understand after, I mean, as long as I’ve been writing dozens of those collections come out every year and, and they, they always, you know, for any writer, they, they’re they sell and they sell, continue to sell.

So I’m guessing that’s just because that’s the most cross denominational title, you know, that something like a rock of ages can be played anywhere. And maybe that’s, maybe that’s why, I don’t know. What’s interesting to me, you know, living here in Nashville, about every other church you go to, you know, it has a praise band and there’s nobody playing piano solos.

So I don’t know where they’re getting played, not Nashville. I’ll tell you that. All right.

Well, so this, this is a question I always ask the arrangers. Does it matter to you whether or not you’re known as an arranger or a composer? Do you think that makes a difference? Well, it does make a difference. It’s funny in the educational market, they would call me a composer in the folio market.

I would be seen as an arranger. And that’s just because people that are teaching those books, see I’ve composed many of those pieces, but I think that delineation tends to be a little more precious to those of us that do it. You know, the general public thinks of you as someone who writes music, but you know, did I answer that question? I don’t know that I did.

It does matter. Well, I mean, cause you said before, you know, the thing about the boxes, you know, getting put in the box. And I wonder if that’s a box that’s hard to get out of.

If you get known as an arranger and then you try to write an original piece, you know, does that, does that present any obstacles? Yeah, I think it does. I don’t know how those played out for me over the years. I’m not really sure I did.

I did more arranging that I did composing. And yet I have a lot of things in, you know, in the, you know, you take that even further, I’ve written dozens and dozens and dozens of songs that have been recorded for various things, but people don’t think of me as a songwriter. Oh, he’s a songwriter.

No, cause I don’t go to, I don’t go to a guitar polls and I don’t hang out in that songwriting world, but I’ve written a lot of songs. So yeah, that’s interesting. I mean, in your own case, have you, have you done specific, like you make a business card, does it say composer, arranger, you know, or does it say arranger? Well, first of all, no one takes business cards anymore.

So I haven’t. No, but I mean, you, you kind of try, but on like on the websites and the bios and that sort of thing, you kind of have to cover all your bases because you don’t want somebody to think that you’re not, you know, if you don’t list, if you don’t list composer, you know, then maybe they won’t ask you to compose something, you know, so you kind of have to kind of, you know, within the industry, no one cares. But I think when you’re looking at presenting yourself to a client, you know, you kind of have to say these, these are the list of services, you know, composer, arranger, orchestrator.

Yeah. I’ve always, my, it always has said composer, arranger, pianist, for whatever reason, that’s what ends up on a lot of my things. And yet I spend at least a third of my life orchestrating and I, I didn’t arrange it, compose it or any of it.

I’m just orchestrating it, you know? And what’s even more interesting to me is how the title of orchestrator is different depending on what town you’re working in. Yeah. You know, in the Christian music business say, we want you to orchestrate this.

What they’re saying is I’m going to send you a piano file and you’re going to build an orchestra around it. You’re arranging it. Yeah.

The piano is just setting out the chord progression and there’s a vocal all been recorded, but you are arranging and orchestrating. But if you’re John Williams orchestrator, you’re essentially a copyist. So it’s, it’s fascinating how those titles are.

Yeah. Well, we didn’t really talk at all about how you got into doing this and how you got into the, the freelance publishing life, but maybe we can just end with if you were starting out now, if you were somebody, you know, fresh out of college and wanting to be selling sheet music, how would you get into it? What would you try? What would you do? I would definitely be taking it as a freelance entrepreneur with a website and a good Facebook and Instagram, social media presence and writing for anybody that would ask me to write, taking commissions and holding onto my creations is the way I would approach it because any of the big labels or publishers that might be listening to this, that, that paradigm is, is changing and changing really quickly. And probably what happens then is you’re as a young person doing the approach that I’m talking about, you’re going to get hired to do things for these other folks based on the work that you’re doing for yourself.

But moving forward, that’s going to be the much bigger field to plow. I’m sure you’re doing the right approach, Garrett. Well, thank you.

Sucking up will take you far. Anything you want to promote before we go? And what’s your, what’s your latest project? I just released to the streaming services, this is a thing called him celebration that I’m really very proud of that I actually created for a label that went out of business. And I have then gotten ahold of the masters and re-released it myself.

And it is eight, 10 minute long symphonic suites for choir and orchestra. So it’s a lot of music. It’s 80, eight times, whatever that is, it’s 80 minutes of music.

And it was something I worked so hard on and it’s meant to be something that can be performed by a symphony and a choir, but it also has congregational things built into it. And yeah, that’s something that I feel fortunate to have been asked to write it. And I’m glad that it’s out there now.

Awesome. And where can people find you? Philip cavern.com. Beautiful. Well, thanks so much.

This was a lot of fun. And we’ll have you on again sometime. Thank you.

My thanks again to Philip for coming on the podcast. Here’s two of his recent works. First up is piano dreaming.

And finally hymns of praise and worship by Philip cavern.