Ep. 9: The Future of Sheet Music is Bright: Interview with Roger Emerson

Episode Description:

Today’s podcast features the legendary Roger Emerson! With over 30 million copies sold, Roger is the most widely performed composer/arranger of popular choral music in the world. He has more than 900 titles available in print through Hal Leonard, but is also involved in self publishing music through his website rogeremerson.com which makes him the ideal person to talk through both sides of the industry.

Featured On This Episode:

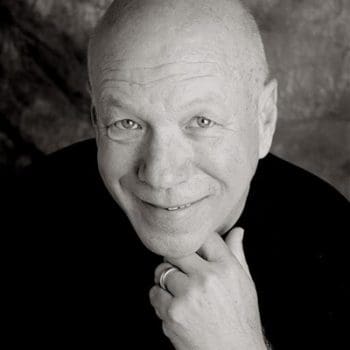

Roger Emerson

Roger Emerson, a professional composer and arranger with over 900 choral titles in print and over 30 million copies in circulation, is the most widely performed composer/arranger of popular choral music in the world today.

Episode Transcript:

*Episode transcripts are automatically generated and have NOT been proofread.*

Let’s start with the question I’m sure everybody always asks you, and that is, how do I get my music published? When you’re in school, it kind of seems like this secretive, mysterious process that nobody really understands.

Well, the reality is there was a time when it was. I mean, it still sort of is a bit of a mystery. Right place, right time, right product remains sort of the default.

But of course, with ArrangeMe, as you know, which you use quite extensively, there’s now a publishing platform for all arrangers to to basically use for the majority of titles. And there’s still titles that aren’t there. But there’s 3 million titles on ArrangeMe.

If you can’t find something to do there, then I don’t know what to tell you. Well, and that’s one of the reasons I wanted to talk to you, because I don’t think there’s anyone out there that has more in print than you. And yet I still see you doing your own self-publishing things on your own website.

I’ve seen you throw some things on ArrangeMe. So I guess how is it that you can have 30 million copies in print and you still feel the need to self-publish? Oh, man, this is a tough question. Well, quite frankly, you’d think I would have enough clout to get anything published.

But there are a couple of things that I’ll tell you the back story. One had to do with musicals. For years, we would do school musicals along with John Jacobson, a good friend for 40 years.

And of course, some of the market for those diminished somewhat when MTI started doing Broadway Junior and all of those, which I think are terrific, a little different price point. But the musical in particular, Zombies, at the time, Emily Crocker was the director of choral publications, and she thought it was too edgy. Now, of course, if you see the show, it’s not edgy at all.

And once Disney did a zombie show, then suddenly it’s fair game for anybody. Well, at that point, John and I decided, hey, let’s go ahead and try our hand at self-publishing. And so we went ahead and it was about 15 grand by the time you get done with a good recording and well-edited print and stuff and put it up digitally.

Of course, it occurred just before the pandemic. So in some ways that helped us because people, it was all digital. They could download and do the thing.

And we gave them permission to do it, to use the tracks and do it virtually and those kinds of things. And then J.W. Pepper showed interest. Of course, we have to discount it to them.

So they now have it in their wheelhouse. And yeah, we finally broke an even and making a little money on it. Self-publishing.

I’m sorry. There’s it’s I know there’s some people, Jake Runestad, for instance, a lot of commissions. Of course, he gets commission money and then he sells and he works it real hard.

He’s at all the conventions and things. But generally speaking, as you probably know, self-publishing is not a big moneymaker. I don’t think even Deke Sharon, who, of course, has put up all of his stuff on Arrange Me, I don’t know what his income is there.

But other things on occasion I have put up because I wanted to get them out quickly and the publisher wasn’t prepared to turn them that quickly. But now we have a new choral team at Hal Leonard that is I think we’re going to see at least Hot Pops go up more quickly or in some venue more quickly. We also have an agreement now with Hal Leonard when it comes to the Arrange Me platform and royalties.

So, yeah, either it’s speed or sometimes one person’s decision not to publish you or something that is available only digitally. For instance, the James Taylor tune that I did as a commission. Oh, it has slipped my mind, but it was available for digital print, but not for actual print.

It’s something that is in, I think, the Alfred wheelhouse. But since I’m exclusive with Hal Leonard, I couldn’t do it through Alfred. So, yeah, it’s the secret of life.

This is something I’ve always wondered about the traditional print publishers, if you will, or I don’t know what you want to call them, the major publishers. Why is it that they’re so selective with the digital only titles? Because you would think there’s not very much overhead and they could put out hundreds and hundreds of digital print titles and it wouldn’t really cost them anything. I mean, is it a marketing thing? Is it a matter of brain space? I mean, I’m a little surprised that hasn’t exploded to the extent that you might think it would.

Well, the two major pop print traditional publishers are Alfred and Hal Leonard. There’s a couple of reasons. One is I think they want to maybe somewhat protect their print business and their exclusive writers that have been paid advances that they wish to recoup.

But the other thing is that it still takes person power to edit, make them look good and to put them up and those types of things. But I think you’re probably going to see digital rights exploited more and more because they are basically non-exclusive. Do you have any sense of how much of the industry is print versus digital at this point? Yeah, right.

It expanded dramatically during the pandemic, but it’s still, I’m going to say five percent, maybe 10 percent of total sales would be digital. Of course, now that audio is MP3 only, you know, that’s going to be growing because you can’t get it in any other format. But people still like the tactile nature of print.

And so I think even in book publishing, where I thought digital would be the end all, be all, I think 60 or 70 percent is still traditional print. Wow, that’s surprising to me. But I guess if you think about where it’s being used, schools and churches, that sort of thing, you’ve got people together.

I’ve always said that digital will take off in schools when we get a cheap iPad, indestructible, lightweight. And I think the subscription, which will ultimately be the way to go, you’ll pay a set amount and you’ll have access for like Netflix. But it’ll take those inexpensive readers, again, that are lightweight to hold and you can mark them and all that kind of thing.

So you see the subscription model as sort of inevitable then? Yeah. And it may not be the only way you get music, but it will be one way in which you can for $295 or $195 have access and maybe access to X number of tunes and that type of thing. So it’s hard to see how it will shake out.

I mean, you can already get a sheet music on How Leonard’s Pass, which I think is what, maybe $70 a year or something. There are various discounts and there’s a lot of choral music on there. But then you’ve got to have for every student.

I mean, think about that. You’re going to spend more money than you are on print. I noticed on Pass a lot of the choral titles and a lot of your titles showing up during the pandemic.

Has that led to more people singing your music? You know, it’s hard to tell. It’s hard to tell from a variety of standpoints. Realize the pandemic was such a free for all, so to speak.

And of course, print sales were off 50 percent. And I was one of the lucky ones at 50 percent. Some were far worse.

And now it’s pretty much back to normal. And it’s really hard to tell when you sell a print copy and you get a percentage, five percent of the retail selling price. It’s pretty straight ahead.

The whole digital thing is a little murky. And of course, it’s not that I don’t think the publishers are honest, but it’s you get just like a lump sum. Sometimes it’s detailed.

It’ll say digital. It’s just it’s hard to track. And quite frankly, I haven’t done analysis of it.

I sort of look at the bottom line and go, hey, if I’m staying even or getting back to even, my income has been sort of consistent for 20 years. And I think, quite frankly, print sales, because everyone’s doing it and there’s a lot out there that the numbers have dropped off. But because there’s an increase in retail selling price, it stayed about about level and it’s about double what I’d make teaching, probably at least in a public school.

Maybe the university would be about the same. So how do you feel about the fact that anyone and their mom can now publish something and compete with you? I mean, how does that change your perspective or I guess your strategy as a composer? Well, there’s two sides to the coin. One, as an educator, I’m delighted.

I’m delighted, number one, that people who have been arranging anyway can be legal. Right. That’s a good thing.

And yes, there’s competition, but everyone does a little bit differently. I feel like people know when they get an arrangement of mine, it’s going to work because that’s all I know how to do, because I’ve always arranged from a teacher standpoint. I was writing and arranging to fill a need.

That is still my end all be all when I’m working on a piece. Who’s going to sing this and how hard is that going to be? And is it worth the trade off to make it either just like the original in some cases or to push those ranges? How hard is the teacher going to work in how many situations to have that bring about a fulfilling, successful vocal experience? And are those things coming to you from Hal Leonard? I mean, are there set guidelines of like tenors can only sing in this range and so on? Or is that just you understanding how it works and doing it yourself? Yeah. Occasionally in our Discovery series, which is sort of designed for middle school, there are some strict parameters, you know, that third part F to D. And if you go outside it, you better be able to tell Audrey Snyder why and she’ll want to cue it.

So it can be daunting sometimes. And again, for me, I’ve tried to encourage them to say male voices, tenor based voices seem to be changing earlier. Maybe we should change those parameters or provide more options.

Again, I think middle school, if we had the advantage to digital, is the ability to change keys, which I think as the voices change and the group you have that year is different. One size doesn’t fit all. I also want to comment on you said whether or not more people have been singing my music during the pandemic.

I think more people had seen me on Zoom during the pandemic. I was getting more gigs now, whether I want them or not, and requests than I ever have. So I say I’m like Betty White.

Hang around long enough and people will like you and appreciate you. But yeah, it’s actually been good for my brand, if you want to call it that. I can’t say that I don’t work at it, but it’s not the end all be all.

Write good charts, pick good songs, try not to wreck them. And everything takes care of itself. Well, I would call it a brand because I feel like the only way to be successful with so much competition is for people to know what they’re getting when they buy from you.

So I don’t think it’s wrong to think of it in that context at all. Going back to the difficulty thing, that’s one of the hardest things, I think, for arrangers to figure out is how to place a piece within a specific difficulty level. Do you have any thoughts on either specific rules or just generally like how you figure that out? Well, the reality is that the difficulty paradigm is a pyramid.

And the best groups are up at the top of that pyramid and they are the smallest market. So if you’re going to make a living writing and arranging, write easier. The big thing is, does it have integrity, even though it’s easy? There’s a terrific choral piece, Craig Heller Johnson’s Requiem.

And if you take a look at it, it is the essence of simplicity. And yet it is so beautifully choral. And to me, I go, yes.

And I tell this story. I’ve got this little book called Choralisms for anyone who wants to read the backstory about a hundred people, little short chapters, little shameless plug there. And you can get it on Amazon.

It’s like 19 bucks or something. But it’s as close to a memoir as I ever do. But in there, I talk about a very, I want to say, green light moment for me.

And that was it’s got to be 25 years ago as an ACDA in San Diego. And it was the Toronto Children’s Chorus singing Bach’s Bistu by Mir Unison. And it was that, Roger, you love thick chords.

You grew up vocal jazz, four freshmen, high lows, Manhattan transfer, New York voices, all this thick harmony. And yet it’s not about the thickness of harmony. I mean, that’s one element, but it’s beauty of line.

And it just cemented in me that you can move people with simplicity. And of course, if you look at my writing, generally speaking, I don’t write much difficult music. And when I do, I always try and as a singer first, make sure the lines that I approach, those cluster chords in a way that is logical and with voice leading and things.

And it wasn’t a class I ever took. It’s just what I want to sing that. Could I sing that when I sing a small group and do some Dharmon meter? And I think Dharmon meter is one fabulous arranger.

But I go, man, that line is hard to get. And I can go over and over and over. It’s still hard to sing.

And, of course, separates me from good people like Dharmon and Peter and all those people. So what I hear you saying is that it’s about the difficulty of the line more than anything else, because I feel like you can have things that are easy with lots of divisi. Like divisi in of itself doesn’t necessarily make something hard.

Right. But it could be the voice leading. It could be the ranges.

It could be the rhythms. Yeah. How’s that divisi approached? I mean, and what is.

Well, I did a little three part mix thing called Rainstorm. And it’s got this chordal harmony. But basically it’s just note, note, doubled on keys.

Right. And suddenly got this Eric Whitaker kind of chord. But it was the way I approached it.

I mean, I love those thick harmonies. I love the add nines and the minor seconds and all that. If there’s a way that I can get to them again, logically, every arrangement is like a concert.

It needs to start somewhere and go somewhere and end somewhere texturally. So, yeah, it’s always a I mean, a wonderful challenge to have. You know, I’m grateful every day that I get to do this.

This is my forty fifth year. And of course, I talk concurrently, at least part time up until about five years ago. And I love that, too.

But there there is something about the puzzle of getting things to where and some pieces just set better than others. Sometimes I’ve gotten done with the piece and go, well, I did my best, but it’s just And other pieces surprise you and go, wow, that that just lays just right or the keys just right. And occasionally I’d go back and go, I wish I’d keyed that a little differently or treated that a little differently.

I take great solace. My friend Paul Lavender at Hal Leonard is sort of John Williams right hand person. And he goes, John Williams, well, he’ll go out and conduct a symphony and do the Raiders, the Lost Ark theme and go, I want to do it this way.

I want to change this. He’ll pass out parts that are different and you go, what, John Williams? Yeah, I think so. What you’re saying is conductors never stop changing it.

They never grow out of it. Never grow out of it. Well, it is the printed page is not music.

It’s a guideline, a map. And everyone has to sort of decide what their way is. And sometimes I’ve heard a teacher do something or a conductor do something.

I go, oh, what a great idea. Why didn’t I think of that? You know, my Shoshone love song. I’m really delighted.

These days that many have asked, can I change? I have he and she sung simultaneously. And now they’re saying, can I substitute the word they? And I said, absolutely. That’s I wasn’t something I thought about.

Right. 35 years ago. So when you’re doing a piece and you know that you’re going to arrange it or have it available in multiple voicings, what is the most efficient way to do that? Are you doing all the different voices in one finale file? Are you doing like a save as I mean, what do you do to save time and effort? Because you’re going to repeat a lot of material.

But I would assume you have to have different files for each version at some point. Well, first of all, in most cases, the SATB is the primary voicing, we call it. And so when I could use a template, but I don’t, I build a new one every time I chose.

I know something about my process. And my first thing is I have to decide, am I going to be close score essay on one staff TB on the other, or is there going to be counterpoint going on? So let’s open it up. The nice thing is that with the editors at Hal Leonard, they will close it up or do it.

Whatever is going to look good on the page and hopefully keep pages to a minimum because it costs more to add pages, you know, to write. So anyway, I’ll do the SATB voicing on the piano part in the optimum key and setting, and I’ll just save it as whatever the title is. All I want for Christmas is you or whatever.

And then I actually will just add staves for all the additional voicings on that primary finale file, and then I’ll call it all I want for Christmas plus revoicings. And then I will do whatever the publisher and I agreed on. You know, it’s usually a two part because two part sells well, not just elementary schools, but people who think it’s easier, which it may or may not be.

I have some real qualms about doing two part with mixed voices. I think it’s a funky sound. There’s a way to treat it, but I’d rather have you do easy three part mix or SAB works better anyway.

So I’ll do the SAB or three part, sometimes an SSA or TBB or something if it really has an appeal there. And so it’ll just be additional staves and I’ll just label them and then the publisher will extract. If I was going to sell, I would, of course, just save them as a different file and with a different file name and make them look as good as you can on the page.

So take us behind the scenes. Do you suggest songs to Hal Leonard? Do they assign you titles? What is the back and forth that happens before you start writing? And then what are the steps that happen after you finish your arrangement and you send them the finale file? First of all, it’s sort of a joint effort. I keep an ongoing list.

I’ve got a list over here and sometimes you pitch a tune and I don’t think so. We got something like that or Kirby did something like that last year. Mac did it or so.

Normally, in fact, I just came from meetings at Hal Leonard because we have a new team in place, but I’m delighted about good people that really get what’s going on. But primarily I pitch songs in the spring and summer and then get rolling about August and write real heavily through December in preparation for, again, a spring promotion and then summer sales. That’s sort of the general thing.

But if they get a big title, Dear Evan Hansen title or Greatest Showman or a Disney thing, then I’ll often get an email that said, hey, would you like to do such and such? I wish they’d said, I’d like you to do Bruno, but no one knew that we don’t talk about Bruno, whatever would be the hit. I did the Family Madrigal, which is a good tune, probably a better tune, but it wasn’t as big a seller. Surface Pressure and We Don’t Talk About Bruno, whatever it’s called, Mark Reimer lucked out, sometimes the luck of the draw.

You know, in Dear Evan Hansen, I chose Waving Through a Window over You Will Be Found because I had a lot of ballads that year. Mac did a fabulous job of it. It’s a great tune and it outsold Waving Through a Window two or three times.

You know, you’d think after 40 years in the business, I would go, ah, this is the winner here. It was a harder tune for one. And so at that point in time, hey, we have these titles, which one would you like? Sometimes it’s a publisher going, well, you’re not recouped, we’ve paid advances to you and so we’re going to give the top title to try and get people even with the board.

And sometimes it’s who calls in, who sends an email first. We’re trying to get away from that into being a judicious kind of, because Mac, Mark, and I, Mark Reimer, Mac Huff, and myself at Hal Leonard are the primary pop writers. Reece Snyder does some, Kirby does some, Alan Billingsley, et cetera, Jake Narud at time at Shawnee.

But we each have a different take on things. You know, if I think about it, Mark tends to do the sort of edgier, hipper things. I tend to do middle of the road.

Mac tends to do the big showbiz things, but we’re all sort of capable of doing any pop tune. Fact is a good pop tune would sell with a horrible arrangement. So that’s an interesting point.

When it comes to arrangements of popular songs or well-known songs, how much of the sales do you think are driven by the popularity of the song versus what you’ve done with the arrangement? Generally speaking, most of the popularity of the song. However, I’ve had great success with arrangements of older tunes, Africa, for instance, which was 25 years old. And then this new setting of it, Fields of Gold, sold really well for me.

And again, my arranging concept, if it’s a current pop tune, you generally want to make it as close to a sound alike as possible, because that’s what the kids want. And that’s what the teacher’s expecting. But if it’s an older, a good older tune, I like to do it in a new setting.

You know, All I Want for Christmas is You, a cappella, sort of a pentatonix treatment, because Mac had, I think, done a straight ahead sort of a pop arrangement of it back when it was most popular. And so, yeah. Well, that was actually going to be my next question.

And you already sort of answered it. But when do you decide, like, oh, I’m going to do something cool and different with this? You know, I’m going to change the feel or change the style versus when do you feel like you need to keep it to the original? And I guess, do you feel, do you wish you could do more creative things with these arrangements, I guess, is one thing I’m thinking about. Well, I don’t generally if Kate Bush is running up that hill.

I mean, for me, it had enough cool elements in it that I pretty much kept it similar to the recording. You know, it had some background answers and stuff. And I knew that’s what the kids would want.

They just heard it on Stranger Things. I want it to sound like that. And my producer, Alan Billingsley, who does my recordings, said, this sounds better than the original.

I go, oh, isn’t that nice? Yeah. Or maybe this is a better way of asking the question. Is it expected for certain ensembles that arrangements are to be more transformative? If you’re writing something for a pop a cappella group or a show choir or a jazz choir, are they expecting it to be drastically different from the original? Yeah.

And of course, you do a lot of custom arranging. And I think the fact is that most of those tunes, although I know a lot of show choirs do more obscure tunes these days, it seems like and do them well that yes, you’re going to you’re going to expect a, quote unquote, custom chart. And again, that isn’t generally my wheelhouse is if it’s a current pop, I want it to sound like the original, maybe be fleshed out some.

You know, when I did A Best Day of My Life, the bridge worked really nicely. It was sort of a stack, still retained the character. High hopes, same kind of thing.

There was some nice counterpoint I was able to put on the chorus. And it, I think, still sounded like the original. And of course, sometimes the original is just a soloist, so you’ve got to do something with it.

Background voices or flesh out the chorus in big chords or do something and still keep the original feel. But I really do like taking a good tune and doing it in a whole different kind of setting. If you look at my Vincent Starry Nights, Don McLean version, I did it was a vocal jazz setting.

I mean, it could be done by a chamber group or big choir, but those are my favorites. Do you see the lines between those stylistic, I guess, genres of choral music blurring more? I mean, do you see more concert choirs dipping their toes into vocal jazz and other sorts of things? Yeah, absolutely. And there and I say more and more do it all.

There’s so much great stuff out there across the board, particularly vocal jazz buff. I was in Kirby Shaw’s first vocal jazz group and grew up with high lows and four freshmen and stuff. I love when a big choir will do a vocal jazz number in particular or particularly any of those vocal jazz ballads with a nice, thick harmony.

Is it really that different than Eric Whitaker, right? Or Ola Yehla or Morton Lawrenson, for that matter. How does it work with BMI and ASCAP for composers getting those performance royalties? My understanding is school performances don’t generate those, but in certain venues it might. Like, can you kind of just go through the ground rules for when composers should expect to get that and what they need to do to get that? Well, I became a member of ASCAP.

I’m a member of ASCAP years ago. And I don’t know, I generate maybe a couple thousand dollars a year and they call it symphony and concert performances and includes TV and things like that. Occasionally, pieces get picked up, particularly on public television.

There’s just not much money in it for at least my type of choral music. And that’s because you wouldn’t get a performance royalty for a popular song that you’ve arranged because they own the copyright. I would only get it on something like Shoshone Love Song or Stopping by Woods or on a setting of Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel.

That’s a PD tune in my setting. And so and again, K-12 schools are generally exempt from PRO organizations, ASCAP BMI licenses. It was a gift, I think, to K-12 schools.

Although it seems to me you have DJs there and stuff like that. There probably should be a nominal school fee that would help cover stuff over and above just concerts. But you don’t want schools to have to pay any more money than they do.

But certainly colleges, a lot of my stuff gets performed by colleges and that type of thing. So I certainly advise anyone who’s particularly a composer, make sure that you align with with a performing rights organization. But I don’t know if there’s much money.

And I mean, I think for Eric Whitaker there probably is because he’s getting broadcast as well. But you register the pieces with ASCAP. And then is it up to the ensemble to report or do you assist with that? You know, no, I don’t actively assist with that.

I sort of let ASCAP do their thing when it comes to reporting and the various venues, Carnegie Hall and things like that, which I’m sure it’s always been sort of a sampling even for airplay. So and again, it’s not a whole lot of money occasionally. And every quarterly I’ll say, oh, $250 shows up there.

It’s a nice little bump, but it’s such a small part of what I do. Maybe I should work it more than I do because there are a lot of performances. If you’re selling a million copies a year or 750,000, 800,000 copies, it’s got to be performed by someone other than your mother.

Hey, if she can get me a BMI check, then more power to her. Whatever it takes, mom. So this is a deep philosophical question, but do you consider yourself more of a composer or an arranger? And do you think the distinction matters? I am a jack of all and master of none.

I’m really sort of a songwriter, which is even different than composer or arranger. I grew up in Los Angeles and I had a rock and roll band. I was writing and pitching songs from the time I was about 13 years old and I was trying to get a record deal.

And so still, I don’t really think of myself, I didn’t take composition class. I think maybe I took a quarter of composition or something, but I don’t have a composition degree and it’s just not in my way. It’s too, I’m not smart enough for starters, but I do hear, I hear melody and I have enough harmonic facility.

I’m a guitarist. I’m better guitarist than I am keyboard player, but I comp chords on keyboard and I sing lines over the top. And I think that’s what a singer songwriter does.

And then I choralize them. Well, and you see a lot of choral people with an instrumental background, too. I think it’s very interesting how people come from all these different aspects of the industry and end up where they end up.

Yeah. I mean, for me, it all came out of, I literally was pitching songs and not getting any covers in LA. And I came to school and got a degree with a couple of years with Kirby Shaw, unpublished at the time.

And then finished a degree in vocal music at Southern Oregon University. And I came back and teaching and I had a K-8 job and everything was, I was teaching band and choir and guitar and everything was pretty good except my 17th grade choir and they sucked. And I just, I go, and then I stumbled on a piece by Joyce Adler’s called Brighten My Soul With Sunshine.

And it was just had a little moderate melodic part for the guys. And I remember having an epiphany and saying, you call yourself a songwriter, write them a song. I wrote it.

I wrote a couple of pieces. So I did first, We Must Be Friends, which was sort of a little pop song with counter melodies and some triadic chord things going on and a big seller, 75,000 copies the first year. Once I got a publisher and then Sinner Man, setting of a PD tune with a hip sort of cool underpinning.

So it’s always been out of need and just a general musicality. There are much better arrangers. There are much smarter musicians.

I just, but I hear music. Thank goodness. It’s carried, it’s carried me a long way.

And again, I never set out to be, to make a lot of money doing this. It was just out of need. And fortunately the stars aligned and right place, right time.

Hardly anyone else was doing it early on. So I was able, my first year with Jensen Publications after my biggest pieces had been turned down by Hal Leonard. That’s a whole nother story.

Just shows you, right? Composers, arrangers, it’s usually one person going, ah, I don’t like that. Next. But the good news is this opportunity opened up as the new company, Art Jensen, who had been ousted in a power struggle at Hal Leonard, formed a new company and needed a choral arranger, right place, right time, remembered me because I had done some things there with him at Hal Leonard and I did 17 pieces my first year and they were all big sellers.

I mean, I must have sold 500,000 copies first year. Wow. It was just amazing.

I mean, I got my first royalty check. It was $6,000 and I was making six grand teaching for the whole year. And this was half a year.

I literally went to a local, I live in a little town, Northern California. I went to Hap Goodrich at CPA. What do I do? He said, let’s incorporate you.

So, okay. But yeah, it was sort of overnight success in some ways, but I’d finally found the right place for my skillset. And it wasn’t writing, build me up buttercup, which I would love to have done, but I would have been a one hit wonder.

And this has been very sustainable, which is nice. So the industry is so different today. What would your advice be to composers or arrangers trying to break in? Boy, it is, it’s tough.

It is tough as because you’re working it yourself. I would say this though. It is promising in that the old guard is sort of aging out.

Well, let’s be honest, we’re all getting older. So there’s going to be, I’ve been working and I don’t want to say mentoring cause he could have done it without me. Jack Zeno, I don’t know if Jack, he’s now the new associate editor at Alfred, 28 years old.

He sent me some charts and I go, man, these are spot on. And, but he’s a teacher and a singer and has a similar background to me. And I said, you’re the heir apparent.

And so, yeah, I, but he worked it. I mean, he worked at his manuscripts were beautiful and he would go and show them to people like Emily Crocker. And I sent, one of his charts came through and it was a Warner title and I sent it on to Andy Beck at Alfred.

And, but he had everything in place. He had a degree. He was a teacher.

I mean, a choral director of the year, young choral director of the year in Connecticut. And his work was print ready. It was beautiful.

So I would say, make sure your work is great. It looks good. Make sure it’s practical and make sure it’s legal that it has copyright information.

I mean, Jack would go as far as to put information at the bottom of the page, just like the publisher, also available, these voicings and also MP3. I mean, it was like, it looked like a real piece of choral music. And so my advice is do good work.

I think, I think really good work will surface. I think that a platform like ArrangeMe will ultimately become a place, a cult spec place where the publisher, if they’re smart, will be looking at Garrett Bree’s arrangements and going, Hey, this has legs, it will appeal. I think one of the toughest things is for those of you writing for a niche or for a particular group, that’s going to be a harder sell than if you’re thinking about the big populace.

And remember Art Jensen, my first publisher said, don’t forget the little old lady in Kansas with in tennis shoes, playing the piano, no rhythm section. How are you going to make it work for her? One last question before I let you go here. How do you view the overall health of the industry? Right.

We’ve come through all these technological changes. We’ve gone through COVID. I mean, kind of where do things stand and where do you think things are going? What trends do you think composers and even directors and people buying music? What are the trends and the things that you think we ought to be keeping an eye on? Boy, first of all, the pandemic was like nothing we’ve ever seen.

And it’s going to take a while to come back because school programs, it’s interesting, I mean, there’s, we certainly saw the teachers that had relationships with their kids, strong relationships were somehow able to maintain the bulk of them. But even their numbers are down and you’ve got a multitude of things going on. Kids trying to catch up.

So taking more AP classes, for instance, which, which limits their participation in the arts, which I think is penny wise and pound foolish, but that’s an artist talking and people are certainly from an industry standpoint are going back to the tried and true that’s in their libraries. So yeah, they’ll pick a pop tune or so. But, and although the industry seems to be coming back to maybe the low end of normal, I think we’re going to see the next five years more of a return to normal.

And again, no one’s got a crystal ball. And, you know, I wish I could tell you, I’m a big believer in giving kids the whole gamut, including the great choral music that I grew up with, the Randall Thompson and spirituals of Jester Hairston and those kinds of things. I hope we don’t forget those.

At the same time, there’s fabulous new music out there. And a lot of people are writing a lot of great stuff. You got to do some digging sometimes, but I’m seeing some really fabulous arrangements and new Kyle Pedersen.

And some of those people, I think we’re seeing a new generation spring up. Certainly Jake Norwood’s doing great stuff. I love his stuff.

Yeah. So I think it’s quite healthy. I mean, the more people who are creating, the better the chances are of some wonderful stuff.

I mean, again, there’s only 12 notes, but the fact is that people are putting them together in new and unique ways. And my friend, Amanda Hanslick, a former Connecticut ACDA, or who’s president elect of Eastern ACDA, commissions works and Rob Dietz, for instance, I don’t know if you know Rob’s work, obviously did a lot of pentatonics, but his choral stuff I’m digging because it’s sort of a blend of that contemporary acapella and choral. It’s exciting.

I mean, if I were, I still think of myself as a teacher. So when I hear these pieces, like, oh yeah, I want to do that. So I guess, in answer to your question, I think it’s quite positive.

You know, if we don’t get shut down again by another rare disease, I think, I think the future looks bright. And again, I think singing in particular, music, but singing is the salve of the world. Well, thank you for taking the time to talk to me today.

You’re certainly one that’s always been very generous with your time and with your knowledge. So anything you want to plug before we go? Okay. I’m going to plug one piece.

It’s not in print yet. Hal Leonard just got the rights to the Joni Mitchell catalog and my setting of both sides now, which will be out in the spring, may be my finest arrangement whenever you get a tune like that. I felt that way with Smile.

I did a nice three-part setting of Smile here. When you get a tune like that, that stood the test of time, the obligation to do the best work you can. And, and in fact, I started it one way, sort of a jazzy way, and I threw it away and I said, no, I want everybody to sing this.

I wanted to invoke the Joni Mitchell and Judy Collins sound. So the soprano altos have a lot of the melody. But then I also wanted some rich, lush ad nine chords.

And I think I got that great pyramid at the end. Yeah. So if I have to stand on one, I think that might be it.

Anyway, both sides now, there’s my plug. Well, thanks again and good luck with everything. And people can go to rogeremerson.com to find links to all sorts of things.

Yeah, great. And certainly hallenderd.com and you can browse and go to my name and there’s a lot of stuff there, folks. Something for everyone.

Or as John Jacobson would say, something to offend everyone. So, Garrett, good luck to you too, in all of your writing and things. And you’re a major force, man.

You’re the new, you’re the new generation. So good luck. Thank you.

I really appreciate it. Take care. Selling Sheet Music is written and produced by Garrett Brees.

If you haven’t already, please subscribe to the podcast and leave us a review on your platform of choice. You can find transcripts of each episode at GarrettBrees.com. Our theme music is written by Garrett Brees and David Dykstra.